|

Think of a 1970s recording artist once lauded as the voice of his generation. His prophetic lyrics and descants of disillusionment haunted music producers and critics alike, and his enigmatic personality, enshrouded by murmurs of debilitating depression and suicide attempts, promised to cement him as a folk-music hero of mythic proportions.

Based on this description, a few artists immediately come to mind. Jim Morrison. Bob Dylan. Kurt Cobain. The name Sixto Rodriguez, however, would not make the short list. But Rodriguez is the aforementioned cryptic crooner, and the bewitching subject of director Malik Bendjelloul’s first feature documentary, Searching for Sugar Man.

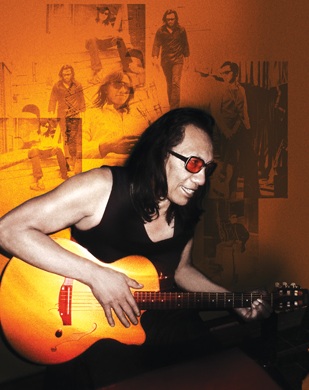

In the late sixties, Rodriguez was an infamous figure in downtown Detroit. He lived a double life, working construction by day and the dive-bar circuit at night. No one could quite decide if he was a homeless drifter or an inner-city poet.

It was during one of these nighttime performances that Rodriguez was discovered, tucked away in the corner of the club with his back to the audience. It’s a testament to the magnetism of Rodriguez’s voice and lyrics that Mike Theodore and Dennis Coffey noticed him at all.

Although these producers had worked with talents such as Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder, they believed Rodriguez’s 1970 debut album, Cold Fact, was the magnum opus of their producing careers.

But the cold fact was that Cold Fact bombed—and so did his second album, Coming From Reality, released a year later. Despite critical success, the albums were a commercial disaster and Rodriguez sank back into oblivion. So why is it that, 42 years later, a Swedish director who had never heard one note of Rodriguez’s music decided to dedicate his debut documentary to the man?

The Stockholm-based Bendjelloul had been directing television documentaries and shorts on musicians for 12 years when he quit his job in 2006 to embark on a sojourn through Africa and South America, searching for a soulful story to carry his first feature.

He found such a tale in Cape Town, where record shop owner Stephen “Sugar” Segerman recounted his role in the rediscovery and subsequent re-emergence of Rodriguez.

Because it isn’t exactly true that Rodriguez sank into total obscurity. Instead, his music drifted to South Africa, where—unbeknownst to the musician—Cold Fact became the anthem for a society oppressed under apartheid. His lyrics, laced with social consciousness and an anti-establishment agenda, taught a generation of listeners to think for themselves. South Africans championed the Mexican- American artist as both a folk hero and a musical genius who, legend has it, was more popular in that nation than even Elvis and the Rolling Stones.

But Rodriguez was completely unaware of his overseas fame. Despite the millions of records sold in South Africa, Rodriguez never received a cent and was cut off from both his fans and his royalties, living below his means as a laborer in Detroit while his spirit ascended to stardom in South Africa.

And fans knew nothing concrete about Rodriguez. All they had were the rumors flickering throughout the country like ghosts, stories of escalating depression and on-stage suicide, and the final mysterious spoken words at the end of his first album: “Thanks for your time and you can thank me for mine. After that’s said, forget it...”

But two fans just couldn’t forget it. Stephen “Sugar” Segerman—who got his moniker from his favorite Rodriguez song and Craig Bartholomew-Strydom set out to find the truth about their hero. What they found fills Bendjelloul’s bittersweet documentary.

South African fans resurrected Rodriguez from musical anonymity, and now, with the Searching for Sugar Man film and soundtrack, it looks like, at age 70, Rodriguez is being reborn for a second time.

After seeing an advanced screening of Sugar Man at Guild Hall, I sat down with director Bendjelloul and the messiahlike Rodriguez for a chat.

Bendjelloul

discusses filmmaking, romanticism, and the

fairy tale of

Rodriguez.

Hampton Sheet: What drew you to Rodriguez’s

story? Was there something that related to your life?

Malik Bendjelloul: Absolutely. I

think it relates to everybody. That’s why people like it. It’s about dreams

and broken dreams, and the resurrection of dreams.

Rodriguez is very inspiring. He didn’t compromise his

life.

Did you expect Searching for Sugar Man to become

such a phenomenon?

I didn’t expect anything. This is

my first movie. But still I thought that this is the best

story I heard in my life. It’s like a fairy tale.

You

hint that Rodriguez lost millions in royalties, but you

don’t delve much into it. Did you opt to leave that

material out of the film?

There’s much more about money

than what is in the movie. It’s a long story. I can tell

you that Rodriguez still sells gold in South Africa. And

he still doesn’t get royalties. It goes to a company in

England. I did speak to them, but they didn’t want to be

in the movie, and they were very reluctant to talk.

Someone should investigate this.

“There is a richness that you receive from the bruisings of society. Life wasn’t meant to be easy.”

How could Rodriguez not know he was famous?

The reason he

didn’t know was that he didn’t get any money.

Normally, you understand you’re

famous in other states because you get royalty checks in your mailbox. It’s

like, “Oh, what is this? All right, I must be famous somewhere.” And he didn’t

get it. The thing about the money is an important part of the story, but it

isn’t crucial…. The story, I think, is another thing, a fairy tale.

There’s a romantic sort of sadness to the film.

Are you a romantic?

What is life if you don’t

look at it with romantic eyes, if you don’t have that kind

of enhancement and think that things matter? That’s what it

is to romanticize something. Filmmaking is romanticizing

reality. Literally. You need to be romantic—otherwise, you

cannot make movies.

How has the film changed your life?

In many ways, the film taught me the same thing as

Rodriguez: Life is difficult for everybody. But Rodriguez

says, “Yeah, I have a hard life, but I made these beautiful,

beautiful songs with my hands on a cheap guitar on my

kitchen table in my ranch of a house in Detroit, and I

changed the world.” He literally changed the world. Everyone

has this possibility. You just try, and you can do

something.

Rodriguez waxes philosophical—and

musical—about fame

and no fortune, and his long, strange

journey.

Hampton Sheet: How does it feel to be in the

Hamptons, where you’re surrounded by so much wealth?

Rodriguez: I’ve been to the Hamptons twice

now. Once, I

had played a place called the Surf Lodge,

and the reason I got the gig was because the owner of the

place is South African. They treated me real well. Drinks

were $17 [each] that’s how the high rollers do it. But it

was still fun. Then we did this Alec Baldwin screening. It

was a great audience, and Alec is a sweetheart. He was a

very, very cordial man. I said to him, “You’re a famous

man.” And he said, “That’s a double-edged sword.”

Has your life changed with the success of the

film?

Totally.

Do you still live in the same house?

Yes, I do.

Do you think you’ll move out when you have your

millions?

Well, I’m looking at that, but I don’t

know if I’m ever going to get that much.

Are you open to monetary success?

You’ve got to have some sort of sensibility…. You have to be

open to that kind of success. I think it’s hard not to

acquire material goods. But that’s not the focus—well, it

shouldn’t be the focus of existence. But it’s embodied

wealth. It’s what you carry with you, and there is a

richness that you receive from the bruisings of society.

Life wasn’t meant to be easy.

Do you feel that success and wealth subtract from

creativity? Do artists need the suffering?

Well, as a Russian writer said, “No tears in the writer, no

tears in the reader.”

So how do you balance that?

When you

find out you share this common experience with

others,

the realization is that you’re not alone. But man is born

alone, he’s thrown into a world of chaos … but I think we

all have a mission, and I think we all decide what that is

individually. There’s no set blueprint for success—it’s

individually decided.

But 40 years later, you’re here.

Yes,

I am.

Did you ever give up?

Well, I was too

disappointed to be disappointed in ’73. After that, I just

kind of left the music scene. But not music. Just trying to

be there at the right place, or meeting the right people … I

just couldn’t kick it with that group.

So you lived a life of hard labor. Where is your

mind when you’re working carpentry and demolition?

Writing music?

It’s almost on automatic. There

are no demands of any kind.

It’s just physical—gross

motor skills.

So your mind is free?

In a way, yes.

You can concentrate or dream of other things.

I think

that we’re always tuned in to our specialties, to ideas, as

writers or as musicians.

One of your lyrics goes, “Maybe today, yeah, I’ll

slip away….” Where were you thinking of going?

In that song, I was just thinking, “Maybe today I’ll make

that decision that will change me.”

Another track, “Street Boy,” mentions street boys

and sweet boys—to whom are you referring?

It’s young boys. Youth. I call them young bloods. They’re

just shaping, and it’s all in front of them now. Society

should provide more choices for young bloods. They should

save social security.

You recorded a lot of your music under the name

Jesus

Rodriguez. But the comparisons don’t stop there.

Jesus was

a carpenter. You are also a carpenter. Jesus is

associated

with parables, and your beautiful songs act as

modern-day

parables. Tell me about that.

That’s a lot to compare to.… I’m a musician. I do music, you

know, that’s my gig. I’m a musico-politico. I’ve written 30

songs, and they’ve surfaced in these last few years and now

with Sony Pictures Classics releasing Malik’s film Searching

for Sugar Man, it’s reignited my music career.

Yes it has! [HS]